Cosmic Insignificance Therapy: A Selection from Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks (2021)

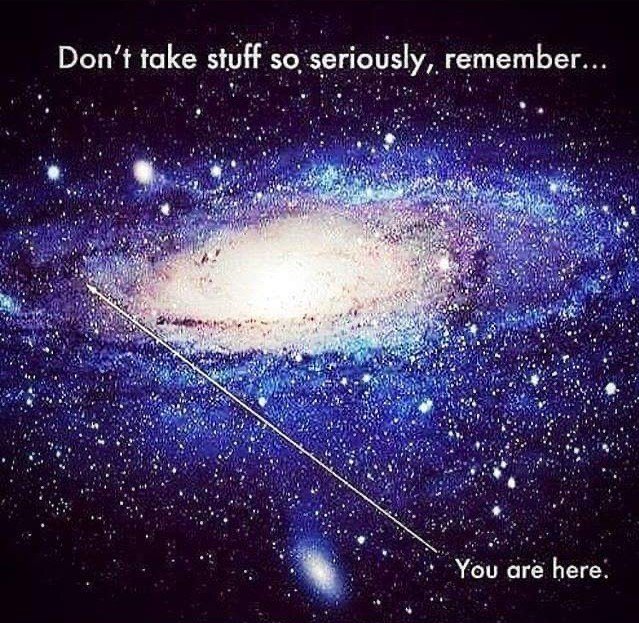

“What you do with your life doesn’t matter all that much—and when it comes to how you’re using your finite time, the universe absolutely could not care less. . . . Your own life will have been a minuscule little flicker of near-nothingness in the scheme of things: the merest pinpoint, with two incomprehensibly vast tracts of time, the past and future of the cosmos as a whole, stretching off into the distance on either side.

It’s natural to find such thoughts terrifying. To contemplate ‘the massive indifference of the universe,’ writes Richard Holloway, the former bishop of Edinburgh, can feel ‘as disorienting as being lost in a dense wood, or as frightening as falling overboard into the sea with no-one to know we have gone.’ But there’s another angle from which it’s oddly consoling. You might think of it as ‘cosmic insignificance therapy’: When things all seem too much, what better solace than a reminder that they are, provided you’re willing to zoom out a bit, indistinguishable from nothing at all? The anxieties that clutter the average life—relationship troubles, status rivalries, money worries—shrink instantly down to irrelevance. So do pandemics and presidencies, for that matter: the cosmos carries on regardless, calm and imperturbable. Or to quote the title of a book I once reviewed: The Universe Doesn’t Give a Flying Fuck About You. To remember how little you matter, on a cosmic timescale, can feel like putting down a heavy burden that most of us didn’t realize we were carrying in the first place.

This sense of relief is worth examining a little more closely, though, because it draws attention to the fact that the rest of the time, most of us do go around thinking of ourselves as fairly central to the unfolding of the universe; if we didn’t, it wouldn’t be any relief to be reminded that in reality this isn’t the case. Nor is this a phenomenon confined to megalomaniacs or pathological narcissists, but something much more fundamental to being human: it’s the understandable tendency to judge everything from the perspective you occupy, so that the few thousand weeks for which you happen to be around inevitably come to feel like the linchpin of history, to which all prior time was always leading up. These self-centered judgments are part of what psychologists call the ‘egocentricity bias,’ and they make good sense from an evolutionary standpoint. If you had a more realistic sense of your own sheer irrelevance, considered on the timescale of the universe, you’d probably be less motivated to struggle to survive, and thereby to propagate your genes.

You might imagine, moreover, that living with such an unrealistic sense of your own historical importance would make life feel more meaningful, by investing your every action with a feeling of cosmic significance, however unwarranted. But what actually happens is that this overvaluing of your existence gives rise to an unrealistic definition of what it would mean to use your finite time well. It sets the bar much too high. It suggests that in order to count as having been ‘well spent,’ your life needs to involve deeply impressive accomplishments, or that it should have a lasting impact on future generations—or at the very least that it must, in the words of the philosopher Iddo Landau, ‘transcend the common and the mundane.’ Clearly, it can’t just be ordinary: After all, if your life is as significant in the scheme of things as you tend to believe, how could you not feel obliged to do something truly remarkable with it?

This is the mindset of the Silicon Valley tycoon determined to ‘put a dent in the universe,’ or the politician fixated on leaving a legacy, or the novelist who secretly thinks her work will count for nothing unless it reaches the heights, and the public acclaim, of Leo Tolstoy’s. Less obviously, though, it is also the implicit outlook of those who glumly conclude that their life is ultimately meaningless, and that they’d better stop expecting it to feel otherwise. What they really mean is that they’ve adopted a standard of meaningfulness to which virtually nobody could ever measure up. ‘We do not disapprove of a chair because it cannot be used to boil water for a nice cup of tea,’ Landau points out: a chair just isn’t the kind of thing that ought to have the capacity to boil water, so it isn’t a problem that it doesn’t. And it is likewise ‘implausible, for almost all people, to demand of themselves that they be a Michelangelo, a Mozart, or an Einstein. . . . There have only been a few dozen such people in the entire history of humanity.’ In other words, you almost certainly won’t put a dent in the universe. Indeed, depending on the stringency of your criteria, even Steve Jobs, who coined that phrase, failed to leave such a dent. Perhaps the iPhone will be remembered for more generations than anything you or I will ever accomplish; but from a truly cosmic view, it will soon be forgotten, like everything else.

No wonder it comes as a relief to be reminded of your insignificance: it’s the feeling of realizing that you’d been holding yourself, all this time, to standards you couldn’t reasonably be expected to meet. And this realization isn’t merely calming but liberating, because once you’re no longer burdened by such an unrealistic definition of a ‘life well spent,’ you’re freed to consider the possibility that a far wider variety of things might qualify as meaningful ways to use your finite time. You’re freed, too, to consider the possibility that many of the things you’re already doing with it are more meaningful than you’d supposed—and that until now, you’d subconsciously been devaluing them, on the grounds that they weren’t ‘significant’ enough.

From this new perspective, it becomes possible to see that preparing nutritious meals for your children might matter as much as anything could ever matter, even if you won’t be winning any cooking awards; or that your novel’s worth writing if it moves or entertains a handful of your contemporaries, even though you know you’re no Tolstoy. Or that virtually any career might be a worthwhile way to spend a working life, if it makes things slightly better for those it serves. . . .

Cosmic insignificance therapy is an invitation to face the truth about your irrelevance in the grand scheme of things. To embrace it, to whatever extent you can. (Isn’t it hilarious, in hindsight, that you ever imagined things might be otherwise?) Truly doing justice to the astonishing gift of a few thousand weeks isn’t a matter of resolving to ‘do something remarkable’ with them. In fact, it entails precisely the opposite: refusing to hold them to an abstract and overdemanding standard of remarkableness, against which they can only ever be found wanting, and taking them instead on their own terms, dropping back down from godlike fantasies of cosmic significance into the experience of life as it concretely, finitely—and often enough, marvelously—really is.”—Oliver Burkeman, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals (2021)